|

| The Tabletop, Watercolor on paper, 2015 ROOM Artspace Gallery, NYC http://roomartspacenyc.com/ |

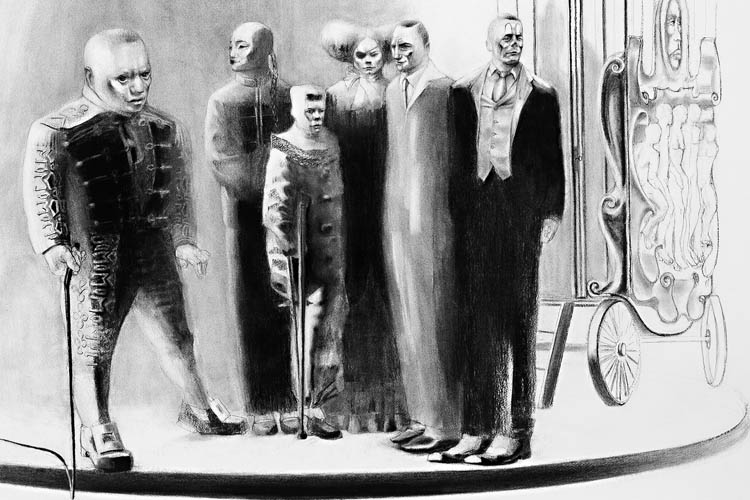

Vanitas in drawings by Lorene Taurerewa. An article by Warwick McLeod

The Victorian photo portrait consciously emulated a rite of the aristocracy to have themselves painted in oils; not just in likeness, but often as their particular fantasy - as a representative of a Universal Truth. They would have themselves portrayed in the guise of an Apollo, for instance, with laurel wreath and harp; or a Diana the Huntress with bow and quiver. By the time early photography came along, painting this way was beginning to look faintly ridiculous. Outside the studio you had coal-furnaces and steam engines massively turning the economic and social gears of the 19th century in a new direction. Brutally, irrevocably, people were being lurched onto huge and irretrievable voyages across oceans, knowing they could never return to kin or homeland. But the same hand that dealt sundering from personal ties and cultural roots held out the offer of social mobility, the prized chalice of status in the new middle-class: and the sacrament of passage from not-so-long-ago-working-class to would-be-aristocracy took place affordably and readily in the photography studio.

This procedure involved extended physical discomfort. The exposure time of a 19th century photograph was several minutes; its subjects would have to stare into the camera, for this time, absolutely motionless, straining every nerve not to move and blur the resulting image. But as these minutes ticked by it must also have been an acutely uncomfortable time psychologically. These faces most often project the pain of lonely minds squeezed in a vise of fear and ambition; lost as to how they arrived at the present except by caprice of history and vague, despised tracks of ancestry; staring at the void of the future under the unforgiving eye of the machine that peels all past from present.

To try to throw a line back to the forsaken past and its comforting traditions, the photographer would diligently attempt to link back to allegorical painting by means of props and backdrops. These still held rich traditions of metaphor. Chief among them was the tabletop: this had been long-established in Painting as a place to gather, arrange, and reflect on certain chosen cherished objects; which, in being dearly possessed, yet remind us of our own possession by the larger facts of time and death, and thus the impossibility of ownership. This was theVanitas tradition, and its soul was an idea called Memento Mori, the Reminder of Death. To this tradition, a tabletop - a plane beneath a void - is the surface of this world, as completely as is a plain beneath sky. On that surface, objects relate, inter-depend, and struggle for independence, in the same various ways as figures on a landscape. A tabletop is a certain model for a certain idea of life on this world: life on the flat-earth plane, without refuge, rimmed by oblivion.

The style of the table can allude more. A kitchen bench or dining table would come with allusions to sacrifice; a large desk suggests worldly, political thought and import. Little tabletops hold knowledge of a particular kind of world; namely the mental world. On little tabletops concentrate the thoughts of secret, unrealizable worlds of wish, dream, and fancy, penned in intimate letters. On little tabletops like these are played little board- and card-games; focusing plots of ruse and stealth in the cast of lots with the world of chance.

No comments:

Post a Comment